Please update your browser.

Findings

- Go to finding 1Organic growth businesses in aggregate generate the majority of small business revenue and payroll, but are also individually the most likely to exit.

- Go to finding 2Financed growth firms may be concentrated in some industries and cities, but organic growth firms abound in every industry and city.

- Go to finding 3Nonemployer small businesses are more likely to exit than to hire employees.

- Go to finding 4New small businesses achieve more stable and regular cash flow patterns over time, or exit.

- Go to finding 5Growing dynamic firms transition from irregular cash flow patterns in different ways, stable firms survive, and dynamic firms that fail to grow exit.

Download

The small business sector, comprised of businesses with fewer than 500 employees, is an important contributor to overall US economic growth. However, the heterogeneity of the sector can obfuscate the ways in which it actually does or does not contribute to economic growth, making it difficult to develop targeted policies to support these contributions.

In this report, the JPMorgan Chase Institute introduces a newly augmented small business data asset to empirically address questions of small business growth, vitality, and economic contribution. We built a sample of 1.3 million de-identified small businesses with Chase Business Banking accounts active between October 2012 and February 2018. The over 3.1 billion transactions we analyze from these businesses provide a novel view of daily revenues, expenses, and financing cash flows for individual small businesses. We use this data asset to develop a revised segmentation of the small business sector, and a new typology of cash flow patterns. These frameworks allow us to inform the contributions of different kinds of small businesses to the US economy, as well as offer new insights about the importance of cash flow management to small business outcomes.

Part I:

The Stability and Dynamics of Small Business Segments

We propose a refined segmentation of the small business sector based on size, complexity, and dynamism, and use this segmentation to identify the contributions of different small business segments to the U.S. economy.

A very small financed growth segment of small businesses attempt to reach a scale-based competitive advantage:

- Intended growth through substantial use of external finance to support asset investments

- May either grow or decline

- Have the potential to make sizable contributions to the overall economy, even though many fail

Many small businesses are stable small employers:

- Most employ 5-20 employees, though some may employ many more

- Are likely to use electronic payroll

There is an interesting and less understood organic growth segment:

- Intended growth through limited use of external finance

- May either grow or decline

- May include a large share of businesses that transition between employer and nonemployer status

The second largest number of businesses are stable micro businesses:

- Typically have no or very few employees

- Provide economic support to large numbers of households of small business owners

Finding One: Organic growth businesses in aggregate generate the majority of small business revenue and payroll, but are also individually the most likely to exit.

Small businesses are dynamic: Six out of 10 small businesses are organic or financed growth firms.

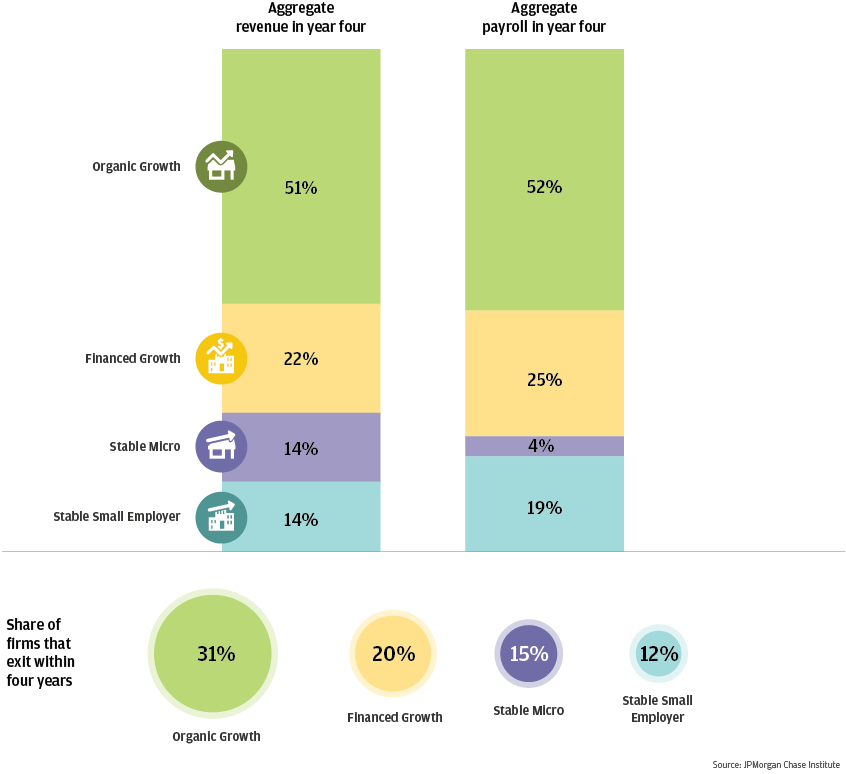

Dynamic small businesses take big risks: 31 percent of organic growth and 20 percent of financed growth firms do not survive four years.

Financing is not the only way to grow: More than half of small businesses are organic growth firms, and they generate the majority of revenue and payroll in the small business sector.

Finding Two: Financed growth firms may be concentrated in some industries and cities, but organic growth firms abound in every industry and city.

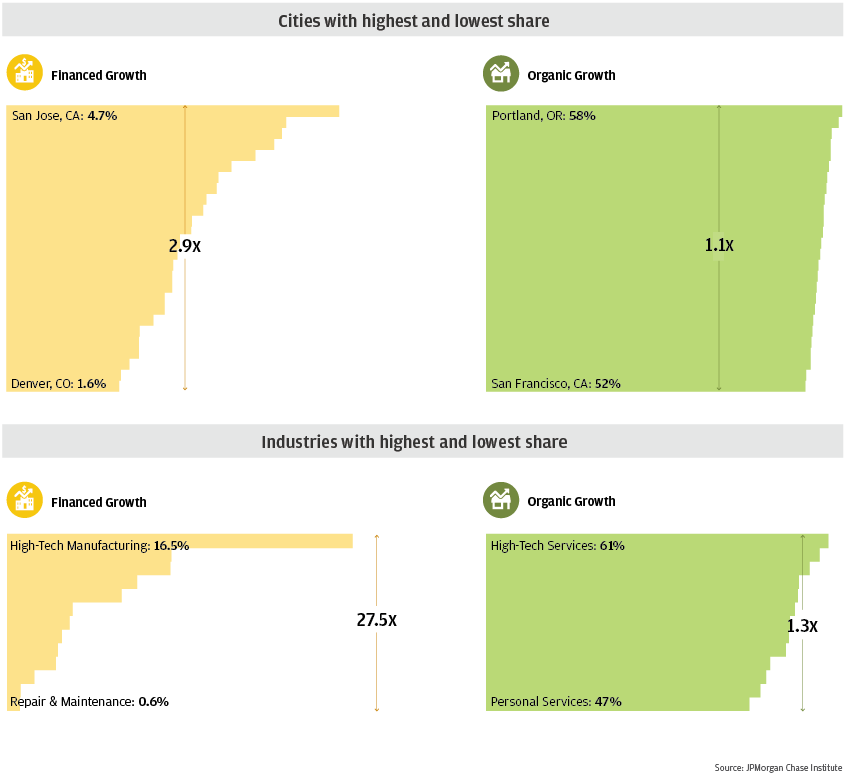

Cities with the highest concentration of financed growth small businesses had twice the incidence of financed growth firms, compared to cities with the lowest concentration, but all cities have large shares of organic growth firms.

Small businesses in high-tech manufacturing are significantly more likely to be financed growth firms, but all industries have sizable shares of organic growth firms.

Finding Three: Nonemployer small businesses are more likely to exit than to hire employees.

We tracked employer status during the first four years of operations for our cohort of 138,000 firms founded in 2013, 5 percent of which were employers in their first year.

Each year, a small percentage of nonemployers become employers, and that likelihood only decreases as firms mature.

Part II:

Cash Flow Patterns and Small Business Performance

We identify seven cash flow patterns that represent different cash flow management problems, and then use these patterns to explore the relationship between cash flow management and small business performance.

Individual firms may experience different cash flow patterns at different stages of their lifecycles. Moreover, some cash flow patterns are more prevalent in some segments.

More Regular Patterns

While few small businesses have very regular cash flow patterns, some patterns are more regular than others.

Larger revenues and expenses occur with weekly frequency, with little deviation in amount or timing.

Very similar to cluster 1, only with high utilization of financing.

Larger revenues occur about twice a month, while expenses are paid about weekly.

Very similar to cluster 3, only with high utilization of financing.

Less Regular Patterns

There are qualitative differences among cash flow patterns for those small businesses with less regular cash flows.

Although the cash flow amounts do not show particular volatility, their timing is very inconsistent.

Expenses are more volatile than revenues, while the reverse is true for most other firms.

Revenues are particularly infrequent, about once every 7 weeks, and the amount varies greatly. Financing is heavily utilized.

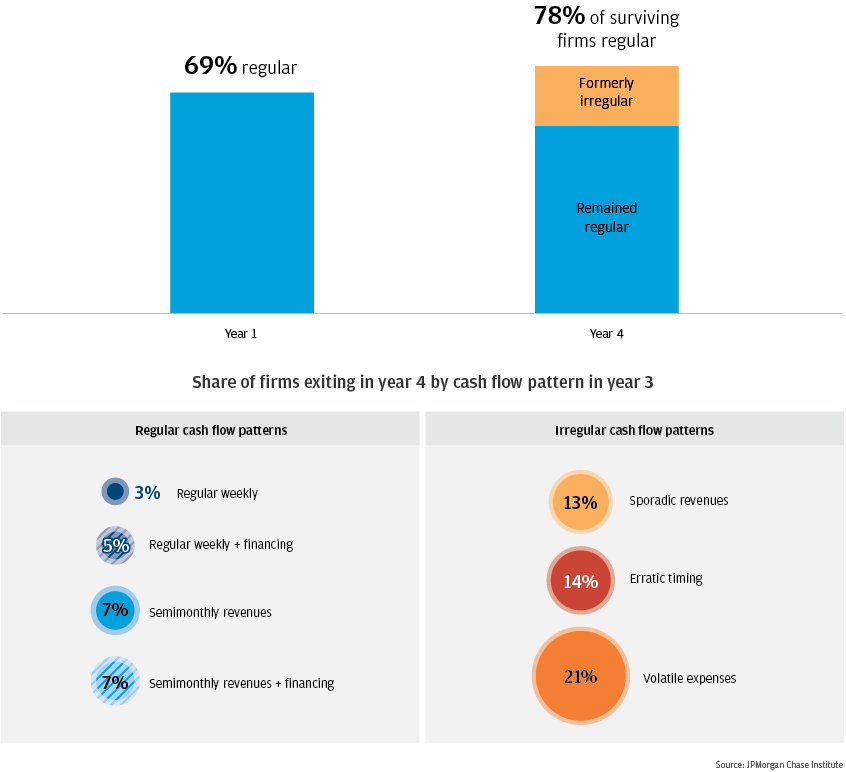

Finding Four: New small businesses achieve more stable and regular cash flow patterns over time, or exit.

Most new small businesses, regardless of their initial cash flow patterns, transition into more regular patterns as they mature.

Small businesses with volatile expenses (relative to revenues) are much more likely to exit than those with other cash flow patterns, suggesting that large and perhaps unexpected expenses could be especially difficult to manage.

Small businesses can and do mitigate irregular cash flows by holding more cash.

Finding Five: Growing dynamic firms transition from irregular cash flow patterns in different ways, stable firms survive, and dynamic firms that fail to grow exit.

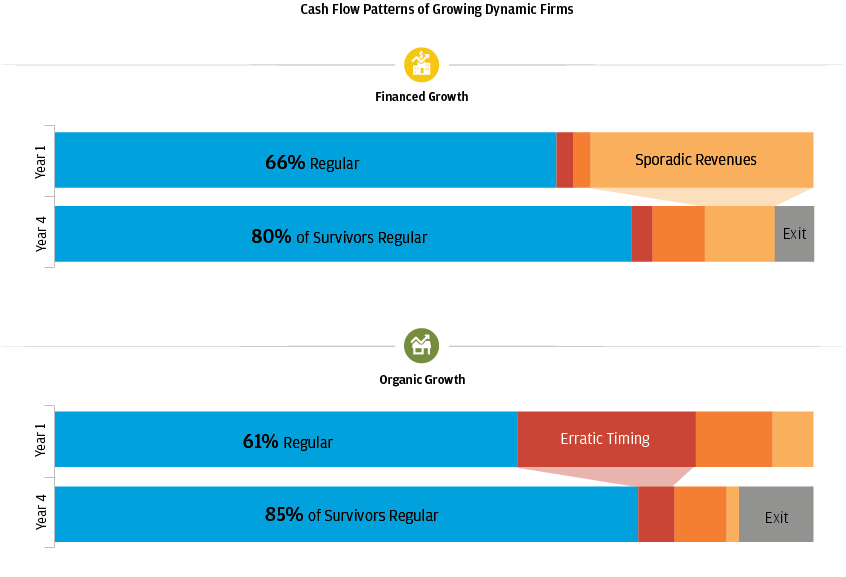

Every small business segment has firms with each of the seven cash flow patterns, but some patterns are more prevalent in some segments, especially as firms mature.

New dynamic small businesses are particularly prone to certain types of irregularity: Financed growth firms are particularly likely to have sporadic revenues, and organic growth firms are especially likely to experience erratic timing of both revenues and expenses. These types of irregularity become less common for firms that grow.

Data

We constructed a sample of 1.3 million firms who hold Chase Business Banking deposit accounts and meet our criteria for small operating businesses in core metropolitan areas. We then used over 3.1 billion anonymized transactions from these businesses to produce a daily view of revenues, expenses, and financing flows for the five years between October 2012 and February 2018.

We also constructed a cohort of firms which opened their business banking accounts in 2013. Firm cash flow patterns and behavior can vary as they mature, and this longitudinal sample controls for age by comparing firms of similar age.

Conclusion

In this report, we brought new data to two conversations about the economic contributions of the small business sector—a first concerning the large contributions of a potentially small set of high-growth businesses, and a second concerning the contributions of the majority of small businesses to widespread and diverse economic growth. We use these data to offer two new frameworks in which to consider these questions—a revised segmentation of the small business sector, and a new typology of cash flow patterns.

Our findings highlight the existence and economic importance of a large segment of dynamic small businesses that grow organically without heavy reliance on external financing. In aggregate, these small businesses generate substantial shares of both revenue and payroll, and importantly, are widely distributed across regions and industries. While the nonemployer small businesses that make up the majority of the sector are unlikely to transition to employer status, many are nevertheless important when viewed through other lenses of economic growth.

Our findings also offer a first high-frequency view of the cash flow dynamics of small businesses. Across the board, small businesses have volatile, irregular, and potentially unpredictable cash flows. Many small businesses transition to more regular cash flows as they age, though many that fail to do so exit. Notably, the kinds of cash flow issues that small business navigate vary meaningfully by segment—financed growth firms were particularly likely to face and resolve cash flow problems related to the uncertainties around revenue, while organic growth firms were more likely to experience a broader array of unexpected cash flow timing.

These findings suggest that policy makers interested in economic growth have an opportunity to focus on a wider range of small businesses than the financing-intensive high growth firms that often are the focus of small business policy, and that opportunities for productive action may exist across a wider variety of regions and industries than previously thought. While the irregularity of cash flow we observe across segments warrants a continued focus on ensuring that small businesses have sufficient liquidity to grow, our findings suggest that programs that help small businesses better manage their cash flows may be equally, if not more, impactful in supporting the overall growth of the U.S. economy.